“…A sizable Surrealist whose highly individual pictures are mirrors of the universal Self.

—The New York Times

Born in Basel, Switzerland in 1900, the Swiss-American Surrealist Kurt Seligmann’s life and work consisted of a fine balance: a gracious respect for his ancestry, past artists, his experiences as a youth, and his studies of magic and ethnographic arts, combined with a pursuit of progression, both in the avant-garde movements and the tumultuous political times within which he lived. His work stands as an amalgamation of an artist keenly aware of and active within his surrounding realities, and on a quest to create a language of characters and imagery to express his intuitions and imaginations.

Seligmann was the first member of the Paris-based Surrealists to relocate to New York in the first months of World War II and was instrumental in helping to rescue many of his fellow artists and intellectuals from Occupied France. From his friendship with Jean Arp and involvement with the Abstraction-Création group, to his induction as a member of the Surrealist circle, to his exile in America and his influence on many of the up-and-coming New York School artists, Seligmann’s rich oeuvre demonstrates the importance of the man and his art in the canon of art history.

Myths and legends have from time immemorial inspired the artist. They contain and express a constant psychological truth. And they lend themselves generously to free associations and interpretations.

—Kurt Seligmann

Early Years

Born in Basel, Switzerland in 1900, Kurt Seligmann's first employment as a teenager was in a local printer's shop and involved learning to apply color to pictures on glass projected for educational use, a skill he would later employ in his own reverse glass paintings. He took lessons from the traditionalist Ernst Buchner and the modernist Eugene Rudolf Ammann, setting a pattern of concurrent and seemingly opposite influences that would continue in his own work throughout his life. In 1918 he started to regularly participate in exhibitions at the Basel Kunsthalle, and in 1919 he began studying at the École des Beaux-Arts in Geneva, where he met Alberto Giacometti. A portrait that he painted of the sculptor at that time now hangs in the Kunstmuseum, Bern.

Kurt's father, Gustav Seligmann, established a successful furniture business in Switzerland, and his mother, Helene Guggenheim, was a member of one of the oldest families in Lengnau; the art collector Peggy Guggenheim was related to the family as well. Kurt's time at the Beaux-Arts abruptly ended when his father became ill and he returned home to assume the responsibilities of running the family business, a role which lasted for eight years. An exhibition at the Kuntsmuseum Basel of the 16th century artist/mercenary Urs Graf was the impetus for him to revisit his artistic pursuits, and in 1926, he resigned from the business. Though it had prospered under his son's management and he had been initially reluctant to have Kurt attend art school, Gustav supported him in the pursuit of his passion and happiness, whatever form that was to take.

Paris and Abstraction-Création

After studying and traveling in Italy for a year, Seligmann moved to Paris in 1929, spending a few months at the school of André Lhote as well as working from models at Colarossi's Académie de la Grande Chaumière and subjects he met in the city. His cosmopolitan life was enriched by frequent visits to the Louvre, his reading of Freud's lectures on psychoanalysis, and the company of other Swiss artists, including Serge Brignoni and Gérard Vuillamy. According to his diary, he purposely sought to find inspiration beyond his intellect and reality, to invent new forms from insight and fantasy.

In 1930 Paris was the epicenter of avant-garde artistic movements, particularly the abstraction groups and Surrealism. Seligmann's style and sensibility demonstrated traits of both genres. The figures within his semi-geometric abstractions set against stark grounds gradually softened to organic forms of strong contrasting color interacting in sweeping curves, which perhaps struck a chord with Jean Arp who invited Seligmann to his studio. Before introducing himself to Max Ernst and André Breton, Seligmann felt he needed to demonstrate his artistic gravitas. That year he was accepted to the third Salon des Surindépendants with paintings and a wood construction. Wolfgang Paalen was among the artists who responded to Seligmann's work, and the two became lifelong friends.

Arp invited Seligmann to join the group he had founded, Abstraction-Création, within which he took active roles, eventually becoming right-hand man to the president, Auguste Herbin, until the group dissolved in 1936. His introduction to Jeanne Boucher by Arp lead to his first solo exhibition in 1932, and thereafter he exhibited in Basel and Bern in shows also featuring Arp.

From the outset, Seligmann's work stood in contrast to the others within Abstraction-Création, with his Surrealist tendencies becoming more evident, and in 1934 he officially became a member of the Surrealist group along with Jacques Hérold, Óscar Domínguez, Richard Oelze and Hans Bellmer. His paintings developed into a unique combination of Surrealism and his Swiss heritage, portraying characters composed of various peculiar shapes and elements. At a show at the Galleria de Milione in Italy in 1935, he exhibited several paintings on reverse glass, employing techniques from his teen years and a traditional Swiss folk art. While straddling the tenets of both artistic groups, the Japanese avant-garde artist Taro Okamoto, with whom he had collaborated, believed that Seligmann was the main cause of the split between the abstractionists and semi-abstractionists which eventually lead to the end of Abstraction-Création.

A Shift Towards Surrealism

The city of Basel had an essential significance within Seligmann's life and work, as he recalled growing up with the image of the 15th century mercenary and the subconscious effect his culture had on his artistic ventures. He affirmed the notion that progress first needs a knowledge of and respect for the past. Most notably, the city's Carnival Day, when the citizens would swarm the streets in medieval costume and lavish headgear in an annual revelry of music and kin, left an enduring impression on the artist. In a 1935 interview, Seligmann recalled:

“My entire childhood was impregnated by the ancient ideal of the Soldier of Fortune which since the 15th century has left an indelible mark on Basel. The heraldic ensigns, the armor, the halyards, the drapery, the ribbons, all this anachronistic attire was very much alive for me. It seems to me that I always hear, in the depth of my ears, the deafening sound of the enormous drums that are reserved for Carnival Day. Basel, you see, is still and always Holbein, Erasmus, Frobeinus, Melanchton. It is in the culture of my natal city to which my subconscious always travels whenever I begin one of my compositions, whether abstract or imaginative.” Héraut, Henri, “Artistes d'aujourd'hui: Kurt Seligmann, peintre d'avant-garde,” Sud, Nr. 126, Marseille, 15 April 1935

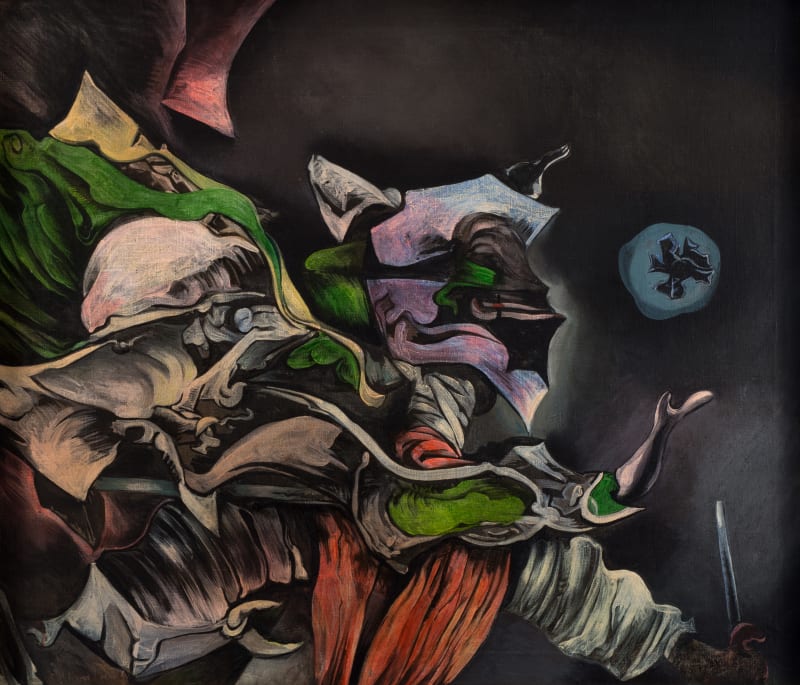

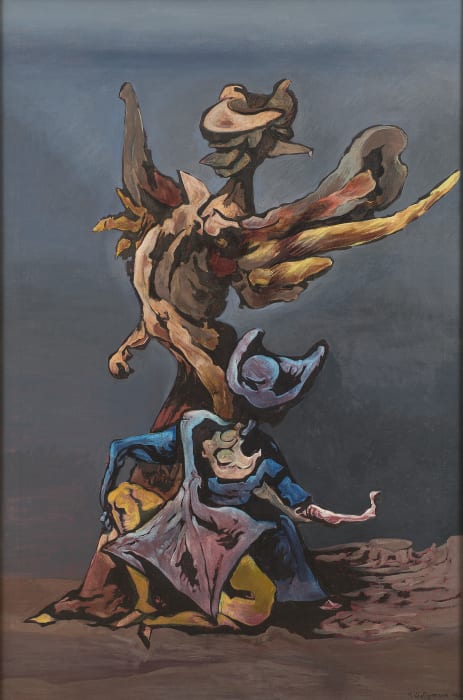

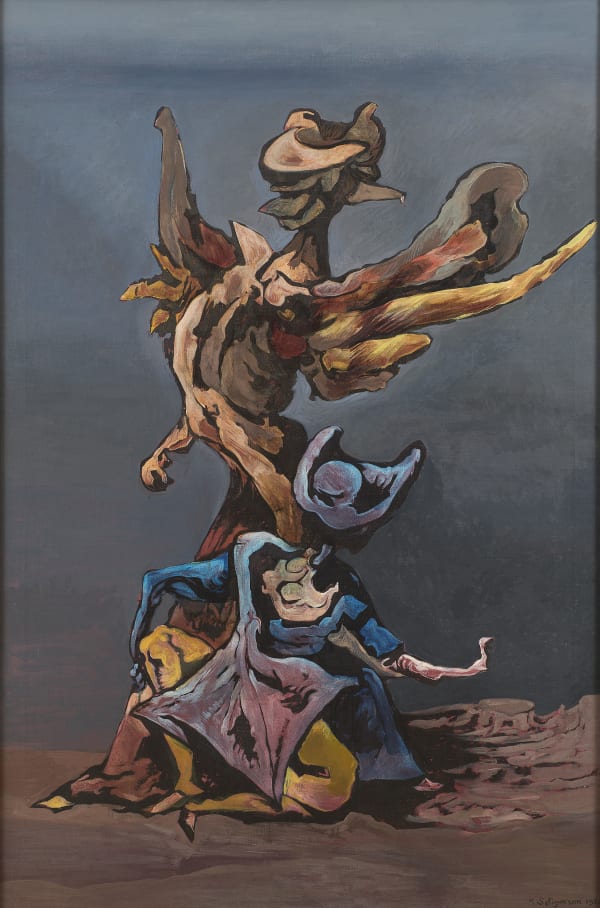

These depictions are most literally illustrated when his characters are in full regalia, engaged in a dance macabre or haunting procession, waving flags or in a flight en masse. Even within his early abstractions and the later anthropomorphic and vegetal compositions, one can detect the heraldic undertones: swaying ribbons of paint, swathes of drapery, a strength in stance and movement. In the essays accompanying the 1961 D'Arcy Galleries exhibition, French Musée d'Art Moderne Director Jean Cassou called Seligmann's figures “truly baroque,” with the “swirling and “undulating” folds of cloth producing “elegant” results. James Johnson Sweeney, Director of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, described his “violence of expression” and “an urgency and fever that brings his work closer to expressionism than to classical repose.” Many observed his relation to his Swiss antecedents, citing the “energy” of Urs Graf (c. 1485-1529) and Nicolas Manuel Deutsch (1484-1530), whose artwork depicted battle scenes and medieval creatures and which can be found reinvented in Seligmann's modern-day combats and fantastical parades. Murdock Pemberton, art critic for The New Yorker magazine, conveyed that “Seligmann reports being especially enraptured by the inner rhythm of battle scenes” of the Italian Renaissance master Paolo Uccello.

In 1935, Seligmann met and married Arlette Paraf, niece of the gallery director Georges Wildenstein, after which they embarked upon world travels together. While in Japan, Taro Okamoto's father organized a one-person show in Tokyo for Seligmann—the first time an artist associated with Surrealism exhibited in Japan prior to the first official International Exhibition of Surrealism in Tokyo, 1937. During their stay at the Hotel Grosvenor in Paris in 1936, Kay Sage, also a guest, discovered Kurt's paintings while peering through an open door. A friendship formed between the three, leading Sage to the Surrealists and ultimately to her marriage to Yves Tanguy.

Kurt and Arlette eventually found a new home and studio in Paris in the Villa Seurat. In 1937, with the encouragement of Tanguy, Seligmann was admitted to the daily meetings of the Surrealists with Breton at the Café Deux Magots, along with Esteban Francés and Patrick Waldberg. Breton wrote in Le Surréalisme et la Peinture, “Kurt Seligmann, who passed through this phase of heraldic symbolism and whose first mission seems to have been to elucidate its mysteries, has moved on to explore all the phosphorescent aspects of the medieval 'night'. From these expeditions he has brought back the pure forms of human anguish and energy…"

A large Surrealism exhibition opened at Wildenstein's noteworthy Galerie des Beaux-Arts in 1938. The exhibition was an experience to be had: a corridor lined with mannequins adorned by the Surrealists, including Seligmann; coal sacks hanging from the ceiling courtesy of Marcel Duchamp; beds surrounding a pond designed by Paalen. Seligmann's earlier works given new Surrealist titles hung amongst those by Max Ernst, Joan Miró, and other Surrealist artists. His objects were also featured, including a soup tureen covered with feathers, a tear-shaped plaster with four human arms, three copies in plaster of a child's portrait bust by the 19th century sculptor, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, and his controversial Ultrameuble—a stool consisting of four female legs in high heels, possibly in a nod to the furniture shop of his past.

Seligmann's involvement with the Surrealists advanced: his collage Les animaux surréalists was included in the Dictionnaire abrégé du Surréalisme published by Breton and éluard; he was among the twelve artists invited by Breton to illustrate the Les Chants de Maldoror by Isidore Ducasse, also known as le Comte de Lautréamont; and his work was featured in an additional Surrealism exhibition organized by Breton and Éluard held in Amsterdam in 1938.

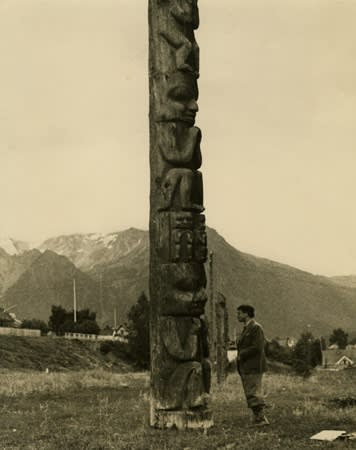

An exhibition of non-European sources of Western art at the Musée du Jeu de Paume in 1937 was of particular interest to the Surrealists, who were intrigued by tribal art. A Surrealist map of the world was presented depicting the largest land masses as those rich in tribal art, and Seligmann, along with many other fellow Surrealists, acquired tribal art objects. What captivated him was the “totemistic substance” of such objects, symbolizing man's connections to primordial life conditions. Kurt and Arlette traveled to British Columbia, spending three months living in a Tsimshian village and observing their life and legends and their parallels to European tales and traditions. They acquired a sixty-foot totem pole that was shipped to Paris and installed at the entry of the Musée de l'Homme.

New Home in America

In September of 1939, following the German invasion of Poland, the Seligmanns departed France by ship for New York. Seemingly the trip was planned so that they could attend his exhibition at Karl Nierendorf's gallery, though the timing indicates this could have been a strategy for them to leave Europe. Seligmann may have anticipated the possibility for a long stay abroad, as the month prior he had sought storage for his glass paintings with Georges Wildenstein which was already occupied. In fact, as early as 1932, he foreshadowed an inevitable war in a scrapbook he had assembled of articles and images.

The exhibition at Nierendorf Gallery, Specters 1939 A.D.—13 Variations on a macabre theme, reflected the current violence of the time while retaining ambiguous elements and those unique to the artist, such as medieval alchemy, classical myths, Swiss devices, and distinctly modern renderings. Upon the show's conclusion, a return to France was impossible, and the Seligmanns moved from the Plaza Hotel annex to a large studio on 40th Street near Fifth Avenue, where they would reside for the following twenty years.

Their relocation to New York and financial stability proved unexpectedly beneficial as Seligmann was able to assist his fellow Surrealists seeking to emigrate from Europe with the threat of impending danger during wartime. He received requests from colleagues, whether they were Jewish or German nationals abroad, and artists whose work was included in Hitler's Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition, for assistance with visas, finances, and reference letters, and he helped to provide affidavits to the Emergency Rescue Committee for Surrealists seeking to depart Europe, including André Masson and Breton. The latter wrote to him from France in 1940, “I am convinced that the future of Surrealism is where you are.”

Surrealist Émigrés

Paalen, who was living in Mexico, wrote to Seligmann in November regarding a show he was organizing with César Moro at the Galería de Arte Mexicano. Breton, who was still serving as military medical staff in France, provided the list of inclusions. Paalen sketched the two Seligmann paintings he wanted to exhibit in the letter to Kurt and informed him that Tanguy had recently arrived in New York. The Paris Surrealists began arriving and regrouping in fall and spring, including Matta, Sage, Duchamp, Masson, Max Ernst, Gordon Onslow Ford and Stanley William Hayter. Their presence led to shows at the galleries of Julien Levy, Curt Valentine and Pierre Matisse, exhibitions at the New School for Social Research, and publications featuring Surrealism. Seligmann was listed as one of the sponsors of View, poet Charles Henri Ford's “poetry paper,” for which he designed a cover and contributed articles on magic.

The 1940s was an active decade for Seligmann. He designed sets and costumes for dance performances, including Hanya Holm's The Golden Fleece and George Balanchine's The Four Temperaments. He exhibited again at the Nierendorf Gallery, the New School, Museum of Modern Art, the Boston Institute of Modern Art, the Addison Gallery, and the Chicago Art Institute. The art historian Meyer Schapiro and his wife Lillian became close friends, and at the suggestion of Lillian's brother, Kurt and Arlette explored and bought a 19th century farmhouse in Sugar Loaf, north of New York City. As it would happen, Schapiro sent one of his graduate students, Robert Motherwell, to Seligmann for painting lessons. In 1943, the Seligmanns took a postponed trip to Mexico at the invitation of the Minister of Education to exhibit at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, which allowed them to spend time with friends who lived there such as Paalen and Frida Kahlo.

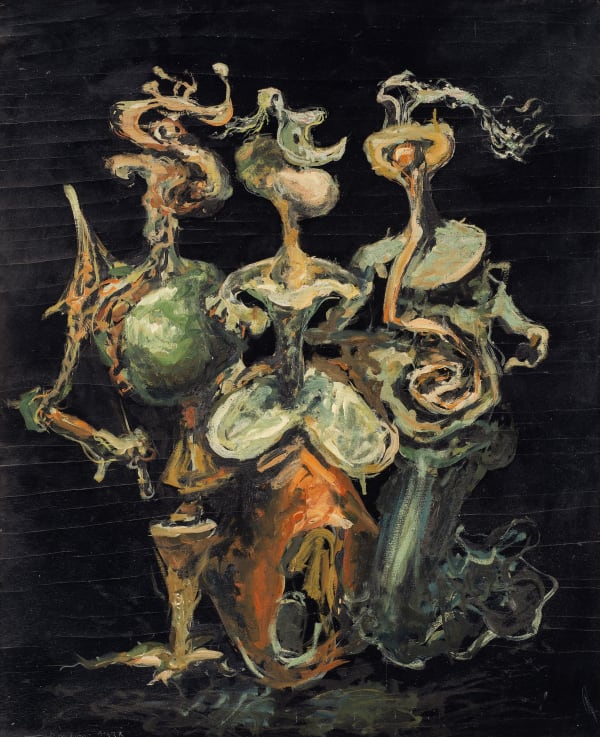

In his personal technique of automatism in the 1940s, Seligmann strove to attain imagery by pure accident so as to avoid repetition in favor of what he referred to as “the a priori element.” Inspired by a method of Hans Rudolf Schiess, he projected fractured glass onto paper or canvas which he then traced for patterns and cultivated cyclonic forms floating or spiraling up from the ground, a fitting vocabulary for his impressions of the awe-inspiring terrains of the Grand Canyon and American Southwest. For the show European Artists Teaching in America at Andover's Addison Gallery, he wrote, “They are landscapes, but they are not static. I call them cyclonic landscapes.” During his exhibition at the Durlacher Gallery the next year, he further expressed, “This is an interpretation of southwestern American landscape. They are psychological landscapes with anthropomorphic elements; living beings seem to detach themselves from tortuous geological formations. A world in formation—not the heroic landscapes of prehistory, but rather a lyrical one.” In contrast to the long histories of his European homeland, this new world held mystery and unpredictability. In his “Prolegomena to the Third Manifesto of Surrealism—or else,” Breton simultaneously wrote about his theory of invisible present beings called “the Great Transparents,” which also may have been inspiration for some of these forms.

The group of Surrealist refugees continued to exhibit and produce artwork together. A series of etchings was printed on a press in Seligmann's barn/studio in Sugar Loaf, which was destroyed by a cyclone a few years later. Duchamp famously fired five shots at the foundation wall of an adjacent barn, then photographed it and printed it with the bullet holes punched out for the cover of the catalogue for the First Papers of Surrealism exhibition of 1942. Seligmann's work was exhibited in that show and at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century gallery. He contributed writings on magic and alchemy to the journal VVV, edited by Breton and Ernst, and the surrealism-oriented View, while accumulating his own collection of rare books on magic. As similar to other Surrealists, he was eventually expelled from the group by Breton, stemming from a disagreement over an interpretation of Tarot cards.

This did not curtail Seligmann's work, and he continued to exhibit regularly. Particularly revealing was the artist's statement to the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1946 for an exhibition titled Eleven Europeans in America, that after briefly experimenting with the cyclonic depictions, his subject matter had returned “to the prevailing interest of my work, which is man.” In the later 1940s his theatrical characters were juxtaposed against architectural backgrounds, similar to Matta's planes, perhaps influenced by his stage design work. While most of his colleagues returned to France after the war, he and Arlette stayed and became American citizens. They kept their house in the Villa Seurat and allowed friends such as Paalen and Noguchi to stay. While they visited Paris for his retrospective at Maeght Gallery in 1949, they were happy to return to their Sugar Loaf farm.

Myth and Magic

Seligmann expanded his collection of books on magic, motivated by a desire to stay connected to traditions of Europe and the printing of his Swiss homeland, and his interest in the link of magic, science and the human psyche.

“I am an artist and I think as a painter. This is the true reason why magic attracts me—the completeness of the magical world. For an artwork should as well be complete in itself. There should be a manifoldness of forms, a variety held together by a coordinating law similar to the magical world law spoken of in clear words by the Babylonians, the Egyptian magis and the Greek metaphysicists…the great philosophers have not been able to break through the magic circle…The great axiom of magic: all is all and all is one has haunted our civilized west and the near east for thousands of years.” View, February/March 1942

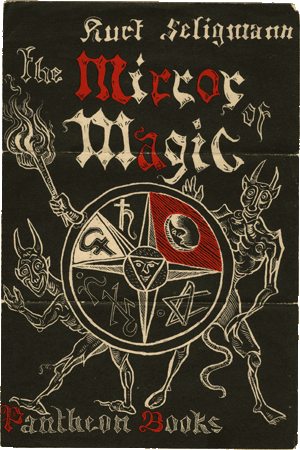

In 1948 Seligmann's own book, The Mirror of Magic, was published by Pantheon; later under the title of History of Magic, it was translated into multiple languages and has gone through many printings. In magic he saw a metaphor for life. “If all is one, there cannot be a separation between man, the stars, and the invisible. There cannot be anything contrary to the world's harmony.”

In the work of the 1950s, Seligmann increasingly invoked vegetal forms, insects, the elements and cosmos, perhaps inspired by the gardens of the Sugar Loaf farm that he and Arlette enjoyed together, and this harmonious ideal which he sought. His new focus of composition retained his classic elements of figure, billowing imagery, movement and energy, applied to references to nature and even Abstract Expressionism.

In 1950 Thomas Bouchard's film of Seligmann working in his studio, The Birth of a Painting, premiered at New York University and was shown for an extended period at the Museum of Modern Art. Seligmann lectured at the New School and exhibited frequently in New York, and in 1954 he was appointed to the Brooklyn College faculty. He suffered a heart attack but soon resumed painting, writing to the author Harvey Arnason, “I am a romanticist. My world is that of dreams, fantasies, apparitions…It is the strange, the unheard of, the exquisite which attracts me…for nothing in the world would I forgo my day and night dreams.”

On January 2, 1962, while he was preparing to shoot the rats eating from his birdfeeder, Seligmann slipped on the icy steps, and his rifle accidentally discharged, killing him immediately. A neighbor coming to pick him up found him shortly thereafter. Arlette passed away thirty years later, and both are buried in the small family plot at the Sugar Loaf farm.

-

An Expansive New Surrealism Show Celebrates 100 Years Of Artistic Revolution

Artnet Oct 4, 2024Featuring more than 500 objects, the Centre Pompidou's 'Surrealism' show explores the global reach and diversity of the artistic movement. Between the rise of artificial...Read more -

Under a revolutionary, emancipatory spell: Venice exhibition explores Surrealism’s interest in the occult

The Art Newspaper APR 2022Major show at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection includes works by leading lights of Surrealism, including Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning Waiting for their visas to...Read more -

Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity Co- Curator, Gražina Subelytė Interviewed

Christie's MAR 2022As the exhibition Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity opens in Venice, its curator Gražina Subelytė talks to Christie's about the role of the occult in...Read more -

Monsters & Myths: Surrealism and War in the 1930s and 1940s at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

Oct 20, 2018As Europe lurched toward fascism and America fought in the Second World War, no other artists produced images more powerfully disturbing than the Surrealists. Monsters...Read more

by Stephen Robeson Miller

-

Kurt Leopold Seligmann was born in Basel, Switzerland, on July 20. His parents were Gustav Seligmann, a businessman, who opened a successful furniture store in 1909, and his wife, the former Helene Guggenheim. They also had a daughter, Marguerite, born 1897.

-

Even as a child, Seligmann demonstrated an artistic proclivity. His earliest extant work is a linoleum ex libris print depicting a helmeted Roman soldier in profile, a subject he would develop in numerous variations throughout his life.

-

Took private painting lessons with two local artists, Ernst Buchner and Eugen Rudolf Ammann. In November of 1918, an exhibition in Basel called Das Neue Leben (The New Life), introduced him to avantgarde art.

-

He exhibited for the first time during the winter of 1918–19 by contributing five works to the annual Christmas exhibition held at the Kunsthalle in Basel. He would also contribute works to this annual exhibition in 1920, 1922, 1932, 1938 and 1952.

His parents tried to discourage his interest in becoming an artist by telling him that it was impractical and that he “would never be Rembrandt.” His reply was, “I don't want to be Rembrandt, I want to be Kurt Seligmann!” As a result, he began to study art formally at the École des Beaux-Arts in Geneva, where two of his fellow students were Alberto Giacometti, who would later become famous as a painter and sculptor, and Pierre Courthion, who would go on to have a distinguished career as an art historian of Impressionist painting. During this time, he painted an oil portrait of Giacometti (now in the collection of the Kunstmuseum, Bern).

-

In February 1920, his father, whose health had deteriorated, demanded that he leave Geneva and return home to assume management of their furniture store. He would remain in this position for nearly eight years, during which time he was unable to work at his painting.

After years of having his artistic aspirations curtailed by running his father's business, Seligmann only became more determined to pursue his passion. He finally resigned from his management position and set off for Florence, Italy, where he enrolled in the Accademia di Belle Arti for the better part of the year.

-

In February, he left for Paris where he rented a small room in the Hôtel des Écoles and enrolled in painting classes at the Académie André Lhote. After a short time there, he decided to pursue the less academic instruction offered at the Académie de la Grande Chaumiére. During this time, he met the Alsatian artist and sculptor, Jean (Hans) Arp, who introduced him to Surrealist art and would become a mentor. Through Arp, he also made the acquaintance of another Surrealist, Max Ernst.

-

Sojourn to Basel upon the death of his father. After returning to Paris, he enrolled in classes taught by the cubist painter Fernand Léger. Examples of his work were accepted for inclusion in a group exhibition at the Salon des Surindépendants. Met the leader of the Surrealist group, André Breton, as well as such abstract artists as Jean Hélion, Auguste Herbin and Alberto Magnelli. Began to develop a personal painting style which included imaginary geometric elements set against dark backgrounds in which one can detect the influence of Arp. In summer, he made a trip to Greece with the Swiss architect Le Corbusier.

-

At the invitation of Jean Hélion and Arp, he joined the group of artists called Abstraction-Création Art Non Figuratif. Members included the likes of Georges Vantongerloo, Naum Gabo, Wolfgang Paalen, Alexander Calder, Antoine Pevsner, Joaquín Torres-García, among some thirty others. A publication illustrating their work and including philosophical statements of each participant was published annually using member contributions, the last of which appeared in 1935.

-

Met Ivy Langton, a naive English artist, who became his girlfriend for the next several years. Had his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris. Exhibited his work at the Kunsthalles in Bern and Basel.

-

His friend Jean Hélion arranged an exhibition at the Galerie Pierre in Paris of his own work and that of Calder, Miró, Pevsner, Seligmann and Arp from June 9–24; the catalogue introduction was by Anatole Jakovsky. Calder later stated in his autobiography that the only line he could remember from Jakovsky's essay was “You don't need a compass in Seligmann's land.” Exhibition of prints at the Zwemmer Gallery and the Mayor Gallery, both in London. The publisher, Chroniques du Jour in Paris, published a numbered portfolio of fifteen of his etchings to accompany Protubérances cardiaques by Anatole Jakovsky.

-

Exhibited watercolors at the Galleria del Milione in Milan, March 8–21. The Paris publisher, Chroniques du Jour, published a second portfolio of fifteen of his etchings titled Vagabondages héraldiques, with an introductory essay by Pierre Courthion. A second solo exhibition of his work was held at the Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris.

-

Second exhibition at the Galleria del Milione, Milan, January 30–February 15.

Exhibition at the Galleria Bragaglia, Rome (April–May). During a summer visit to Geneva, while at the beach on the lake, he met Arlette Paraf (she had been stung by a bee, and he came to her aid). They ended up taking the train back to Paris together, by which time, as she later stated, she knew it (the relationship) was “serious.” They were married in Paris on November 25, the witnesses being Jean Arp and Max Ernst, and left thereafter for a six-month honeymoon trip around the world. Seligmann had exhibitions in Tahiti and Japan along the way.

Contributed three engravings as illustrations to the poem, Flaques, by Jean-Paul Collet.

-

Contributed engravings as illustrations to Pierre Courthion's Métiers des Hommes, published by Editions Guy Levis Mano in Paris.

In New York, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the director of the Museum of Modern Art, included his work in the museum's landmark exhibition, Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism (November–December).

-

Formally accepted into the Surrealist meetings by André Breton, who acquired his work for his personal collection.

-

International Surrealist Exhibition in February, held at the Galerie des Beaux-Arts, Paris, which was owned by Arlette's uncle Georges Wildenstein. Summer spent in British Columbia collecting Indian artifacts on behalf of Claude Levi- Strauss, the director of the Musée de l'Homme in Paris, including a sixty-foot totem pole which was installed at the entrance of the museum.

Joined other Surrealists (Brauner, Domínguez, Ernst, Magritte, Man Ray, Masson, Matta, Miró, Paalen and Tanguy) in illustrating the complete work of Lautréamont, published by Editions G.L.M., Paris.

Contributed an engraved frontispiece illustration to André Breton's Dreams, and a set of engravings to illustrate Georges Hugnet's A Readable Writing.

-

His article, “Interview with a Tsimshian,” based on his findings during the time he spent in Alaska in 1938, was published in the journal Minotaure (Nr. 12/13), Paris.

Arrived in New York in September with Arlette for an exhibition of his work at the Nierendorf Gallery, called Kurt Seligmann: Specters 1939 A.D.—13 Variations on a macabre theme. He was the first Surrealist to be exiled in America. Took an apartment in the Beaux-Arts building at 80 West 40th Street. Began to assist his fellow artist colleagues left behind in Europe to reach safety in the United States. Also exhibited at the New School for Social Research.

-

His work was included in the International Surrealist Exhibition held at Inés Amor's Galería de Arte Mexicano in Mexico City (January–February).

Exhibition of Drawings and Etchings by Kurt Seligmann held in March at the New School for Social Research, New York.

In a gallery at the Museum of Modern Art, he met the art historian Meyer Schapiro, Professor of Art History at Columbia University, and the two became fast friends.

Contributed the frontispiece image to Herodias, a poem by Stéphane Mallarmé, with an introduction and commentary by Clark Mills, published by The Press of James A. Decker, Prairie City, Illinois.

Following a visit to the residence of Schapiro's brother-in-law, Dr. Joseph Milgram, in Marlboro, New York, he and Arlette discovered the nearby hamlet of Sugar Loaf. There they purchased a fifty-five acre farm, with barn and other farm buildings, and its accompanying late 18th century house. This would be their retreat from the city for the rest of their lives and the location of many gatherings of their artist and writer friends.

Taught painting technique and printmaking at Briarcliff Junior College, New York. The future Abstract Expressionist, Robert Motherwell, studied painting privately with Seligmann at the suggestion of Meyer Schapiro.

-

Became a frequent contributor to the avant-garde publication, View magazine, edited by Charles Henri Ford, founded in this year, until it ceased publication in 1948.

Opening of the New York City Ballet production of The Golden Fleece by Hanya Holm in March, with costumes and set designed by Seligmann, at the Mansfield Theatre.

Second solo exhibition at the Nierendorf Gallery, New York (April–May).

Provided the frontispiece illustration for Edouard Roditi's book, Prison within Prison: Three Elegies on Hebrew Themes, published by The Press of James A. Decker, Prairie City, Illinois.

-

André Breton included his work in the exhibition, First Papers of Surrealism, held at the Whitelaw-Reid Mansion, 1042 Madison Avenue, New York, from October 14–November 7. This would be the only Surrealist exhibition organized by Breton in the United States during his wartime exile.

Participated in the landmark exhibition, Artists in Exile, held at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, along with fourteen of his fellow Surrealist and modernist exiles: Berman, Breton, Chagall, Ernst, Léger, Lipchitz, Masson, Matta, Mondrian, Ozenfant, Seligmann, Tanguy, Tchelitchew, and Zadkine. The famous group photograph taken by George Platt Lynes.

Another memorable group photograph in which he appeared was taken at Peggy Guggenheim's penthouse and included Marcel Duchamp, Peggy Guggenheim, Max Ernst, Frederick Kiesler, André Breton, Fernand Léger, Amédée Ozenfant, Berenice Abbott, Jimmy Ernst, John Ferren, Piet Mondrian, Stanley William Hayter, and Leonora Carrington.

He was a frequent contributor to the four issues of VVV magazine (1942–44), André Breton's official publication in America during the Surrealists' exile.

-

Contributed the cover design for the April issue of View magazine, edited by Charles Henri Ford.

Contributed an engraving as the frontispiece to André Breton's Pleine Marge, published by Nierendorf Gallery, New York.

During a meeting of the Surrealist group in New York, while Breton was discussing the significance of the tarot card, Seligmann corrected him about a point he was making. Breton erupted in anger and told him that he was to consider himself expelled from the Surrealist group. Breton returned the works he owned by Seligmann to him and told him he would not be included in any future Surrealist exhibitions. Seligmann was devastated, but, according to his friend Meyer Schapiro, the expulsion did not interfere with his personal friendships with other Surrealists.

Traveled to Mexico in the summer for the opening of his solo exhibition of twenty-one paintings at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, organized by Inés Amor. While there, he and Arlette visited Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Wolfgang Paalen, Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Benjamin Péret, and Gordon Onslow Ford.

-

Durlacher Bros. Gallery, New York, published and exhibited his six etchings illustrating the Myth of Oedipus in a boxed, numbered set of fifty copies with a text by Meyer Schapiro.

His work was included in The Imagery of Chess exhibition held at the Julien Levy Gallery, from December 12, 1944–January 13, 1945.

-

After the war, all of his Surrealist colleagues living in or around New York and Connecticut, except for Tanguy, returned to Europe permanently.

Designed the costumes and stage designs for the New York City Ballet production of George Balanchine's The Four Temperaments.

James Johnson Sweeney, curator at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, included his work and interview in “Eleven Europeans in America,” The Museum of Modern Art Bulletin, vol. 13, nos. 4–5.

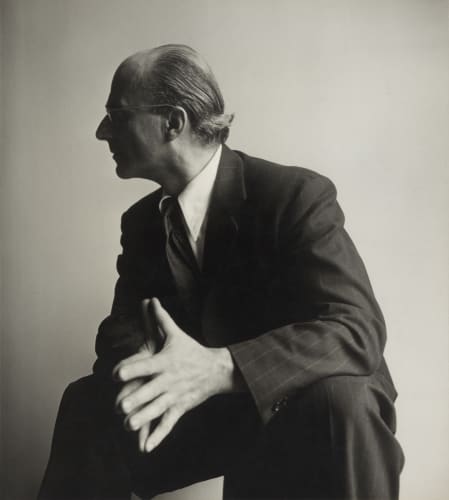

As with many of his friends, such as Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning, and Kay Sage and Yves Tanguy, he and Arlette were photographed by Irving Penn.

Peggy Guggenheim, who had opened her gallery called Art of This Century in New York in 1942, and who owned three works by Seligmann, coveted a 1919 Dada work by Max Ernst in Seligmann's collection. She told him that if he did not let her have the Ernst, she would expunge Seligmann's works from her collection and never exhibit his art again. When he and Arlette said they would not part with the Ernst, Guggenheim kept her word.

-

His work was included in the exhibition, Abstract and Surrealist Art in America, held at the Art Institute of Chicago, from November 6, 1947–January 11, 1948.

-

His book, The Mirror of Magic, published by Pantheon Books, New York, was critically well-received. It would be later reprinted by the same publisher under the title The History of Magic in 1952, and as Magic, Supernaturalism and Religion, by the Universal Library, New York, in 1968. It would be translated and published in Italian, French, German and Portuguese.

Contributed the illustrations to Wallace Stevens' poem, A Primitive Like an Orb, published by the Gotham Book Mart (A Prospero Pamphlet), New York.

-

Traveled with Arlette to Paris in April for a large retrospective exhibition of his work held at the Galerie Maeght. During this sojourn, he visited numerous friends, such as Tristan Tzara, Charles Duits, and César Domela. On this occasion, the gallery prepared a special number of its publication, Derrière le miroir (Nr. 49), about his work, with essays by Charles Duits, Georges Duthuit, Pierre Courthion and Pierre Mabille.

-

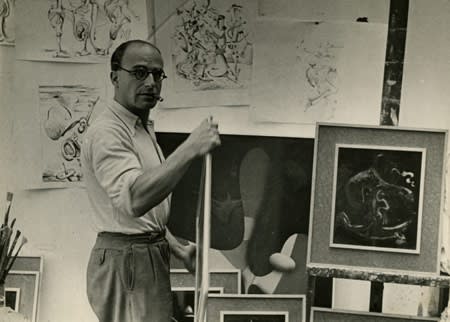

His neighbor and friend in the Beaux-Arts building, filmmaker Thomas Bouchard, made and directed a film about Seligmann called The Birth of a Painting (35 minutes in length; photography by Diane Bouchard; narration by Kurt Seligmann; music by Edgard Varése). First shown in New York on May 25, the film follows Seligmann as he creates a version of his painting Magnetic Mountain. (Since the death of Diane Bouchard in March 2013, two other films made by Thomas Bouchard about Seligmann have come to light).

Solo exhibition at Durlacher Bros. Gallery, New York, from November 7–December 2.

Seligmann organized the American delegation of artists whose work was included in the Third Exposition of Independent Artists held at the Yomiuri Shimbun in Tokyo, Japan, from February 27–March 18, 1951.

-

Taught art at the New School for Social Research, New York.

-

Contributed an extended “A Letter about Drawing” to the Art Institute of Chicago's Quarterly, Vol. LXVI, no. 3, September 15, 1952.

Solo exhibition at Durlacher Bros. Gallery, New York, December 16, 1952–January 10, 1953.

-

Solo exhibition at the Alexandre Iolas Gallery, New York, in February; catalogue introduction by the Greek poet, Nicolas Calas.

-

Taught art classes at Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, New York.

-

On April 1, he became a naturalized United States citizen.

Solo exhibition at Durlacher Bros. Gallery, New York, in November.

-

Solo exhibition at The Fantasy Gallery, Washington, D.C. (February–March).

He left the United States in November for Paris, where he stayed at his Villa Seurat residence, working on a new series of paintings which he called In Full Daylight (En plein jour). He would not return to New York until May 1957.

-

Suffered a heart attack on March 31, from which he spent nearly six weeks recovering. As a result, he canceled the trip he had planned to Paris during the summer of 1958, and gave up the idea he had entertained of making annual trips abroad.

He and Arlette vacated their apartment and studio in the Beaux- Arts building at 80 West 40th Street, and they settled permanently on their farm in Sugar Loaf.

Commissioned by the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, to illustrate The Unicorn, the Gorgon and the Manticore by Gian-Carlo Menotti, produced in concert form by the Center Arts Council in June.

-

Dual exhibition of Seligmann and Max Ernst held at the Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania (February–March).

-

In April, Otto M. Gerson organized an exhibition for Seligmann titled Kurt Seligmann: Recent Paintings at his gallery, Fine Arts Associates, in New York.

-

Retrospective exhibition at the D'Arcy Galleries, 1091 Madison Avenue, New York, April 18– May 13. The catalogue included accolades and tributes about his work by James Johnson Sweeney, Katherine Kuh, Murdock Pemberton, Edwin Alden Jewell, Nicolas Calas, Benjamin Péret, Jean Cassou, Gualtieri di San Lazzaro, Anatole Jakovsky, Aline B. Saarinen, Parker Tyler, and Florence Stol.

Solo exhibition at the Ruth White Gallery, New York.

-

In the early morning of January 2, while preparing to shoot the rats that were menacing his bird feeder at his farm in Sugar Loaf, he slipped on the icy steps of his house, fell backwards, and his rifle accidentally discharged into his head, killing him immediately. A few minutes later, he was found by his neighbor, Charles Shaughnessy, who had come to take him to have his car repaired in the nearby town of Goshen.

His obituary appeared in The New York Times and Die Neue Zürcher Zeitung, among many others. His funeral was held at Conger Memorial Funeral Home, Chester, New York. At his request, internment was at the nineteenth century graveyard near his studio in Sugar Loaf.

-

The D'Arcy Galleries, 1091 Madison Avenue, New York, mounted an exhibition called Kurt Seligmann: The Early Years, January 27–February 15, which included an essay by his old friend Meyer Schapiro.

Coinciding with the D'Arcy Galleries exhibition, Time Magazine ran an article with color illustrations about him and his work, called “Dance without the Dancer” in its January 31 issue, vol. 83, no. 5, pp. 44, 46.